No one should mistake my criticism of how I lost my virginity at the American Boychoir School as a condemnation of the institution itself. A previous post on my website goes into detail here. Followup posts can be viewed here, here and here.

Its founder, Herbert Huffman, dedicated his life to growing a selected cadre of gifted musical boys into a nationally beloved choir in Columbus, Ohio. Huffman oversaw its move and transition to the academically elite community of Princeton, NJ, where boys explored a community where they learned it was acceptable to learn as much as they could – as fast as they can.

That’s quite a contrast to the peer group pressure exerted by boys in Miami’s suburbs of Hialeah and Miami Springs, where I grew up. When I returned there in the 9th grade, classmates asked me not to do so well academically, “because it makes the rest of us look badly.”

I coasted, and made straight A’s. That’s how outstanding my Princeton education was.

More than 50 years after a twisted genius by the name of Donald Bryant orchestrated a loss of institutional control, the Princeton-based Boychoir’s inmates have finally taken over. Some of what transpired was revealed in well-written investigational stories by the New York Times and New Yorker magazine. Boychoir management only sought to quash these sensational revelations, revealing a serious disdain for transparency.

After I wrote my own story here of encountering a sexual predator, I heard enough response to sense a troubling undercurrent of suspicion resided in the surrounding area of Bucks and Mercer counties from women who had married previous members of the Boychoir. The lid of damnation that caused editors to censor stories about the American Boychoir had backfired. Eventually, bankruptcy was the only course the venerable institution had left.

The people I refer to as “inmates” are its new leaders, men who have matriculated through many of life’s pitfalls. They are accomplished in their fields and recognize what the Boychoir meant to them and its potential to future generations.

According to Kris Brewer, spokesman for the resurrection committee, “It is a shared sentiment and goal to make sure that if we are successful … that acknowledgment, transparency, learning, prevention and healing are essential to the success of the Foundation and a future ABS… We are not interested in keeping silent about or hiding the past. It does no one any good now or in the future.”

Chet Douglass and Aaron Smyth are joining Brewer to step forward as a triumvirate and promulgate a concept as time-honored as Christianity itself – a resurrection.

My personal story is meant to bequeath their cause far more than the $10 gift I donated; it is meant to inspire Messrs. Brewer, Douglass and Smyth to continue and persevere.

Back in the winter of 1955, I auditioned for Herbert Huffman, founder of the Columbus Boychoir. I don’t recall much of that audition, except it took place in Coral Gables. I remember Huffman as a gentle soul, whose interest in great music was legendary.

I remember my mother spoke with Huffman privately after I sang for him. I don’t know if she told him about my father, Virgil, but he was a tormented musical genius who once played with each of the Dorsey brothers in New York City, but evolved into a frustrated musician who savagely and frequently beat me for no reason at all.

At home, I had retreated into a private world in which I pretended to be a television programmer. (The quality of my first journalism gig – a TV writer – reveals how much I used media for an escape.) I developed a good singing voice by singing in the shower, and my mother, Thelma, who played piano for the First Presbyterian Church in Hialeah, hoped to get me away from my father’s physical abuse.

I was chosen, an unlikely selection because of the pigment of my skin. During the spring, summer and falls of my life, Virgil took my family to South Beach where we played with other boys on the soft sloping sands along the Atlantic Ocean. The constant exposure of the sun on my skin darkened me considerably; however, brothers Jon and Chris turned red from the exposure and suffered with serious sunburns. I sometimes burned, but kept getting darker and darker.

At Albemarle, where I lived in a dormitory setting with the other choirboys, I never thought of myself as outside the cultural norm until one day. We previewed a never-before-seen video film taken of us while performing a sacred choral piece. Each choirboy – one by one – was paraded before a camera while singing a Christmas hymn. The film was ready and edited with sound, and we were the first to enjoy it.

Because I tried not to care, my nonchalance was rewarded. I never saw myself! But some other boys said they had, so the film was rerun for my benefit. I didn’t see anything distinctive, except for an apparent Negro boy who walked through. I recognized almost everyone else. Who was that black kid?

“That’s you!” the other boys exclaimed. “Look again.”

Once again, the film was rewound to where I walked through. After strong urging, I recognized some of my features. I was the black one!

No way, I thought. What was going on?

After all these years, I think I understand. Because of the lighting used in the newspaper and on TV channels that was specific only to me, I appeared white and Caucasian. Compared to the other boys at the school, though, the camera portrayed me as dark.

Herbert Huffman chose me despite my complexion, because he saw the potential of my musical gifts. I played piano well, and I was a decent second soprano. So Huffman rescued me from my father.

I never revealed these details before, so you, readers of this blog, know them for the first time ever.

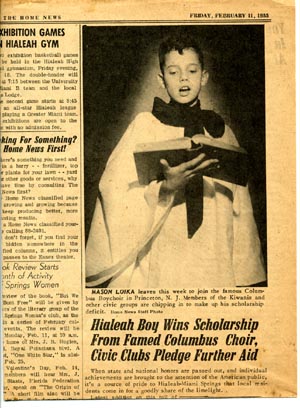

I saved and scanned the official story about me written courtesy of Jay Morton, publisher of the Hialeah Home News who on Feb. 11, 1955, announced my selection to the Columbus Boychoir.

(By the way, Jay Morton was no ordinary publisher. After studying art at the Pratt Institute in New York, receiving a master’s degree in Paris, he had moved to Miami to write and draw the animated cartoon, “Superman,” for Fleischer Studios. He was responsible for describing Superman as “faster than a speeding bullet, more powerful than a locomotive, able to leap tall buildings in a single bound.” He also drew Felix the Cat, Betty Boop and Popeye.)

As publisher of the Hialeah Home News, in the 1940s and ’50s, he ran a one-man crusade to drive the Ku Klux Klan out of Hialeah. He passed away on Sept. 6, 2003, the same day as my late brother Jon’s birthday. I am proud to share the text of his article verbatim, especially because it contains no typos, as follows:

When state and national honors are passed out, and individual achievements are brought to the attention of the American public, it’s a source of pride to Hialeah-Miami Springs that local residents come in for a goodly share of the limelight.

Latest addition of this roll of honor is little Mason Loika, son of Mr. and Mrs. Virgil Loika, 810 N.E. Third pl., Hialeah. Mason left this week for Princeton, N.J. where he won a scholarship at the nationally famous Columbus Boychoir School.

Mason looks like any other boy who is almost 12. His brown locks have a tendency to be unruly with a cowlick indicating, as the saying goes, bedevilment. But just let Mason don his choir-robe – a long, black, monk-like skirt, a white, wide-sleeved tunic, and a big, black bow under his chin …

Then he’s transformed into an angel, and surely sings like one.

That’s what Herbert Huffman, director of the Boychoir, thought when he auditioned Mason at the University of Miami two weeks ago. Huffman and his boys’ ensemble were here for a concert, and the Loikas felt fortunate when he consented to hear Mason’s voice.

Their joy was irrepressible when Huffman offered the boy an $800 scholarship at the non-sectarian school. But finance reared its ugly head. A year’s tuition, room and board, costs $1,600. The Loikas could raise $400 on their own, but where was the other $400 coming from?

That’s when Mrs. Loika came to the Home News (he is a Home News carrier) to pick up Mason’s papers. The story came out, and Publisher Jay Morton resolved that, if he could be of help, this opportunity and honor would not be bypassed.

Morton has been on the phone soliciting support from the city’s civic organizations and this week when Mason departed it looked as though his dream would come true. The pledges aren’t all in yet, but the Loikas are proceeding on faith.

Mason’s father is now employed at Pan-American, but he has 25 years as a professional musician behind him. He gave his son all the training he could. Mason’s mother, a music-teacher and music instructor for kindergarten, has been giving him piano lessons.

At Princeton, Mason will have a regular curriculum which will cover at least what he’s learning now in the seventh grade at Hialeah High. He’ll also have choir practice twice a day, plus individual voice training.

The Columbus Boychoir is renowned throughout the country. Besides appearing at festivals and secular gatherings, the boy choristers have been heard on national hook-ups of radio and television, and in recordings. They were on Ed Sullivan’s “Toast of the Town” at Christmas. They always “bring the house down” at every concert they appear in.

Just as Mason won applause at the Kiwanis club luncheon on Tuesday. While his mother accompanied him, his childish treble rose in melody and he won the hearts of the Kiwanians.